Posted by Jacqueline Beggs @JacquelineBeggs

“Not every decision needs to be green Mum” came the aggrieved voice of my teenage son about a decade ago. I do not remember what prompted the gripe, nor my response at the time (probably something lame, as fathoming the psyche of teenagers was not my best parenting skill). His lament has lingered with me, but here is how I would like to respond now: “Yes, they do – all our decisions need to be green. The world’s environmental challenges are too dire to start picking and choosing which times we make a green choice and which times we carry on regardless.” To be fair, this same son, 10 years later took time off work to be on the front line of the recent Extinction Rebellion climate change protests in Wellington!

I was one of more than 11000 signatories on the 2019 World Scientist’s Warning of Climate Emergency. Not only does this highlight the perilous and imminent danger of climate change, but also it outlines six immediate steps we need to take to make a major difference. From reducing the use of fossil fuels and sequestering more CO2, to stabilising human population growth, we need to act now. However, it is not just climate change I’m concerned about; it is the accelerating loss of biodiversity, the intensification of agricultural impacts, the overexploitation of resources, rampant urban development, the pollution of our land and waterways, and the continuous arrival and impact of pests and disease. Many of these issues interact, requiring solutions that are multi-pronged and take a holistic approach. For example, while planting and maintaining trees is critical to reducing levels of CO2, if we focus on planting native rather than exotic species then we also support our native biodiversity. And if we plant the native trees into a fenced area that forms a buffer between cows and a waterway, then in one step we sequester CO2, enhance native biodiversity and reduce nutrient runoff into our waterways. Perfect!

Despite a lifetime committed to researching and communicating these issues, I have a sense of failure that it has been too little, too late. It is not enough just to keep warning folk of the catastrophic effect humans have on the planet; scientists also need to “Walk the Talk”. We need to demonstrate with personal action that we believe our own data and warnings. Physicist Shaun Hendy led the way in 2018 with a year of no flying, documented in his new book #NoFly.

So, beyond what I do professionally, here are what I consider my top three personal actions to contribute to a more sustainable future:

- Reduced intake of meat and meat products. Producing meat is environmentally costly. Humans need to undertake a dietary shift to eat mostly plants and fewer animal products. For me this is a work in progress as I am down to just one or two meat meals a week. My “Not every decision needs to be green Mum” son is now way ahead of me on this with his plant-based diet.

- Reduce and mitigate carbon footprint. I favour walking where possible (the adolescent in me sometimes jumps onto a Lime scooter), but I mostly commute by bus. Air travel is trickier. Academics are frequent flyers as we connect with scientists around the globe, particularly when on research and study leave as I have been in 2019. To mitigate my extra travel this year, I calculated the air miles I have travelled (15,000 miles) and therefore the amount of carbon I generated (8000 pounds (3.63 tonnes)) so I could estimate how many trees I need to plant to offset my emissions (240 trees). A local landowner allowed us to fence off stock from a wetland, and to date this year I have planted 47 native trees into this restoration project. Only 200 trees to go!!

- More environmentally sustainable clothing choices. The pollution generated and resources squandered on clothing is mind boggling. It is complex to calculate the total environmental footprint of textiles, as it needs to include factors such as the pesticides and land used in farming cotton, pollution from manufacture (toxic dyes and other chemicals), waste from discarded clothing, and shipping. Op-shops are my friend as I have transitioned my wardrobe in the last decade or so to predominantly second-hand clothing. Most of my choices are low maintenance items that require no ironing (OK – that is more about laziness than saving electricity by not using an iron) and rejecting fast fashion by selecting items that will stand the test of time. The current standout is a top my mum made me when I was 17. Technically a “new” item in my wardrobe, but I have been wearing it for 40 years!

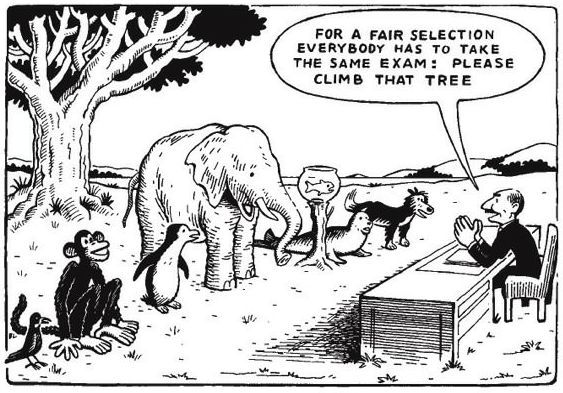

The environmental challenges we face are massive if we want the world to remain habitable for humans and retain biodiversity. For example, to keep global warming this century below 2°C, then we need to reduce our personal carbon footprint to 1.5 t per person by 2050. Around 70% of carbon emissions are actually made by just 100 companies, so is it worth the sacrifice to try to reduce your personal footprint when it is a minuscule drop in the bucket of what is needed? To me yes; everyone needs to engage in reducing their environmental impact, but we also need to demand systemic change away from GDP growth and the pursuit of affluence. Our goals should be to sustain ecosystems and improve human well-being. We need to act now.

Jacqueline Beggs is a Professor in Ecology at the School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland. She is Director of the Centre for Biodiversity and Biosecurity and leads the Faculty of Science “A Sustainable Future” research theme.