The demise of long-term population monitoring

Posted by Margaret Stanley @mc_stanley1

“Is there any evidence that an introduced insect – other than a social insect – has caused the decline of a native species in New Zealand?”

A feeling of total frustration and helplessness came over me when I heard those words – while standing before an EPA panel deciding whether to allow a generalist insect predator into New Zealand for biocontrol of a crop pest.

The answer to this is “no”. The frustration comes from the fact that we have no evidence, because there is no long-term monitoring of native insect populations in New Zealand. The Dept. of Conservation (DoC) may have data for a few threatened species (perhaps wetapunga?), but not for common insect species – those that might follow the fate of the passenger pigeon if an additional invasive predator is the thing that tips the balance for that population. The example I gave the EPA in answer to that question was anecdotal – the decline of our native mantis as a result of the invasive South African mantis. There’s certainly no long-term population monitoring that has picked up the demise of the native mantis.

The lack of long-term monitoring for non-charismatic species (e.g. bees) has also been lamented in Europe lately, where a massive decline of insects in Germany over the last few decades has been detected by the Krefeld Entomological Society: a group of mostly amateur entomologists, recording insects since 1905. They have recorded declines of up to 80% since the early 1980s – that’s a lot of bird food (if you care only for vertebrates!).

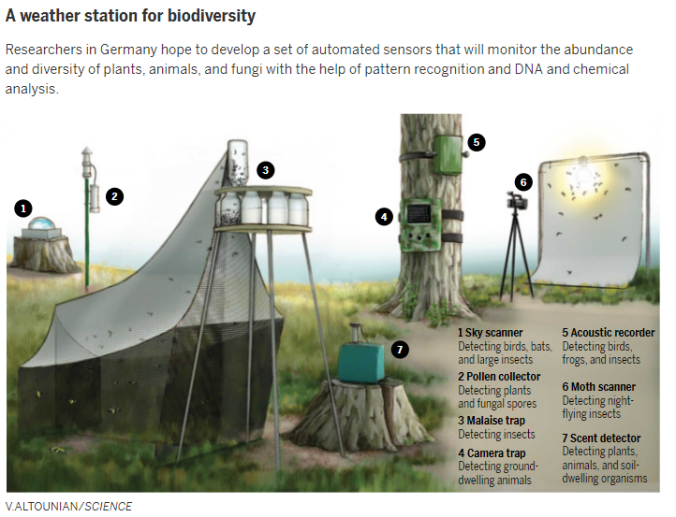

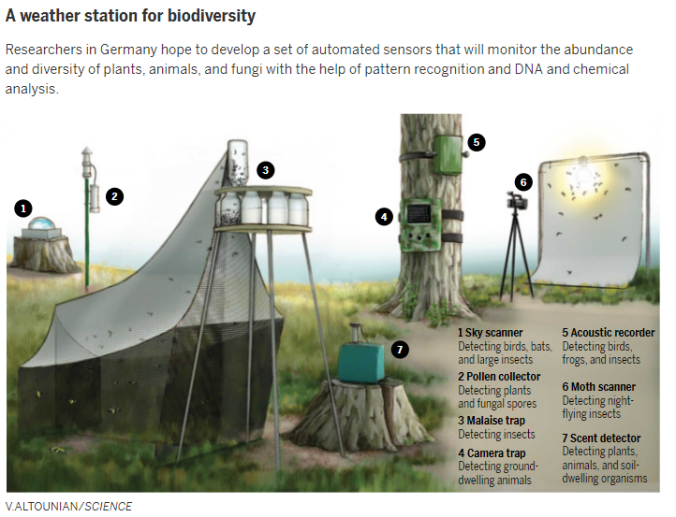

Plans for long-term biodiversity monitoring in Germany (Vogel 2007)

Changes in science funding over the last few decades, and the vagaries of politics, means that long-term population monitoring is no longer ‘sexy’ and not worthy of funding (‘Cinderella Science’: unloved and underpaid). These types of datasets are difficult to maintain because they exceed cycles of funding and government administration. In New Zealand we now lament the loss of amazing datasets that have provided the foundation and impetus for some amazing science around ecology, conservation and pest control: e.g. the Orongorongo Valley dataset, and the long term monitoring of wasps, pests and birds in Nelson.

DoC and some councils do undertake regular biodiversity monitoring where they can, but on a reduced number of taxa (usually birds and vegetation), not often at a population level (except for threatened species), and the data are often held within these organisations, rather than open access sites. Some scientists also try to sneak in a long-term monitoring project where their (often unfunded) time and resources allow.

Instead, community groups in New Zealand, those groups undertaking pest control and restoring ecosystems, are taking up the slack in long-term ecological monitoring. At least for vegetation and birds, they are the ones undertaking regular and long-term monitoring via vegetation plots and bird counts. There is also the rise of citizen science – with large numbers of people recording biodiversity: counting kereru and garden birds. Although scientists are doing what they can to give community groups technical advice, and make citizen science more robust, will the data being collected be robust enough to understand how disturbance, invasion, and climate change are affecting biodiversity? Community restoration often takes place primarily where people are (close to urban centres), and restoration projects are dominated by lowland coastal forest ecosystems. Hardly representative of New Zealand’s ecosystems.

Needless to say, there was great excitement within the ecological/entomological community with the initiation of NZ’s National Science Challenges. The idea was mooted that we could have a Long Term Ecological Research network (LETR) like that funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) in the USA. This network of sites provides the research platforms and long-term datasets necessary to document and analyse environmental change. There are numerous papers that summarise the benefits of long-term ecological datasets, such as: (1) quantifying and understanding how ecosystems respond to change; (2) understanding complex ecosystem processes that occur over long time periods; (3) providing core ecological data to develop, parameterise and validate theoretical and simulation models; (4) acting as platforms for collaborative, transdisciplinary research; and (5) providing data and understanding at scales relevant to management (Lindenmayer et al. 2012). Surely gaining an in-depth understanding of New Zealand populations and ecosystems over time would allow us to understand their resilience to the effects of long-term and large-scale drivers like climate change, and even the effects of new invasive species, such as myrtle rust?

However, it was not to be. And although citizen science and community monitoring is valuable in its own right for specific purposes, it doesn’t allow us to respond to the opening salvo.

If an insect goes extinct in the forest, will anyone know?

Postscript: The EPA decided not to allow import of the predatory insect – not so much because the ecological risk was perceived to be particularly high – but the industry benefits were seen as too low relative to the risk.

Dr Margaret Stanley is a Senior Lecturer in Ecology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland and is the programme director of the Masters in Biosecurity and Conservation. Her interests in terrestrial community ecology are diverse, but can be grouped into three main research strands: urban ecology; invasion ecology; and plant-animal interactions.

Dr Margaret Stanley is a Senior Lecturer in Ecology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland and is the programme director of the Masters in Biosecurity and Conservation. Her interests in terrestrial community ecology are diverse, but can be grouped into three main research strands: urban ecology; invasion ecology; and plant-animal interactions.

Cathy is a MSc student in the Centre for Biodiversity & Biosecurity, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland. She is investigating the impact of hedgehogs in urban forest fragments. She is supervised by Margaret Stanley and Al Glen.

Cathy is a MSc student in the Centre for Biodiversity & Biosecurity, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland. She is investigating the impact of hedgehogs in urban forest fragments. She is supervised by Margaret Stanley and Al Glen.

Dr Margaret Stanley

Dr Margaret Stanley