Posted by Margaret Stanley @mc_stanley1

In an earlier blog (What’s the Point of Urban Ecology?), I talked about the importance of urban ecosystems – both for connecting people with nature, and for their intrinsic values. Cities can be biodiversity hotspots!

Maximising biodiversity in the streets of Paris

There are the usual suspects that come to mind when we consider threats to urban biodiversity: human population increases, intensification, climate change, etc. But are there any new threats on the horizon that we should be looking out for in cities? With this in mind, we applied for funding for a horizon-scanning exercise to identify emerging threats in urban ecosystems (thanks CBB!). Horizon-scanning is a systematic search for issues that are not widely recognised – either in the research literature or in policy.

In January of this year, we brought together 12 participants from Australia, UK and New Zealand for the horizon scanning workshop. We based the workshop on the well-known conservation horizon scanning workshops led by Prof. Bill Sutherland. Before coming to our workshop, we used our professional networks to gather ‘emerging threats’ from colleagues in science, policy and management. During the workshop, we explored, debated and ranked the 137 potential threats that were suggested by the global experts.

Debating the issues during the horizon-scanning workshop

The key to this exercise was to identify threats that were truly on the horizon, rather than one of the ‘usual suspects’. It was remarkably difficult to really pull out those ‘good grief’ moments as Prof. Kevin Gaston called them – the potential threats that truly surprised us. The workshop was a refreshing opportunity to do something we scientists rarely get an opportunity to do – delve into issues completely outside our knowledge set. Who would have thought we’d be trying to figure out what human ‘cremains’ are composed of? Or google-searching ‘self-healing concrete’?

The paper resulting from the workshop has been published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. The final list of potential threats (see below) included advances in technology, as well as issues around how people are using green spaces. It is important to recognise that although we’ve identified potential threats associated with new technology, some of these new technologies also bring a range of environmental benefits (e.g. solar panels). The main purpose of horizon scanning is to identify potential threats early, so we can assess whether they really are a threat, and if so, mitigate the threat proactively. It’s possible that just ‘tweaking’ a piece of technology would reduce its impact on urban biota, while maintaining its effectiveness.

So what’s next on the horizon?

Ecologists are often accused of being negative (or even “scare-mongering” to quote a journalist who interviewed me this week) – perhaps our next horizon-scan should search for emerging opportunities for urban ecosystems. That sounds like a much more inspiring workshop!

In the meantime, we hope to inspire researchers to explore how much of a threat these 10 issues are, and to inspire policymakers and managers to look ahead to threats on the horizon.

TOP 10 Potential threats:

Maximising biodiversity in the streets of Paris

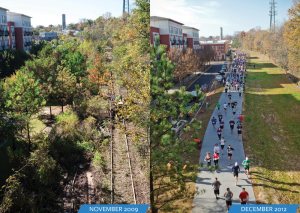

Health demands on greenspace: As more people are encouraged to use green urban spaces for exercise, these spaces can become highly maintained for people rather than wildlife; with more tracks, artificial lighting and fewer plants.

Digital replacement of nature: There is a risk that nature in cities could be replaced with digital equivalents of nature, such as images and sound recordings. This gives people some of the benefits of nature, but without the maintenance and messy side of nature, however it could lead to city dwellers undervaluing nature in their immediate environment.

Digital replacement of nature: There is a risk that nature in cities could be replaced with digital equivalents of nature, such as images and sound recordings. This gives people some of the benefits of nature, but without the maintenance and messy side of nature, however it could lead to city dwellers undervaluing nature in their immediate environment.

Scattered cremains (material resulting from cremation): There has been a growing trend for cremation as space for burial of human remains is at a premium. However, in some cities land for interring cremains has become very expensive and scattering cremains has become more culturally acceptable. Because of high levels of phosphate and calcium in cremains, there is a risk of polluting urban ecosystems and waterways.

Spread of disease by urban cats: Globally, there are now more than 600 million pet cats, and the increase in pet cat ownership is resulting in the disease toxoplasma spilling over into wildlife populations, in urban areas as well as to species in more remote locations, such as the endangered Hector’s dolphin.

Spread of disease by urban cats: Globally, there are now more than 600 million pet cats, and the increase in pet cat ownership is resulting in the disease toxoplasma spilling over into wildlife populations, in urban areas as well as to species in more remote locations, such as the endangered Hector’s dolphin.

Switch to LED lights: Cities across the globe are switching their lighting technology to LED lights. However, the whiter spectrum of LED lights overlaps with the visual systems of wildlife and can disrupt their physiology and behaviour.

Switch to LED lights: Cities across the globe are switching their lighting technology to LED lights. However, the whiter spectrum of LED lights overlaps with the visual systems of wildlife and can disrupt their physiology and behaviour.

Solar cities: Many cities are implementing city-wide solar panel installation programmes. However, solar panels can disrupt the behaviour and reproduction of animals that are attracted to the polarised light they produce.

Nanotechnology: Nanoparticles (e.g. graphene) are now an increasing but invisible part of cities, found in everything from smartphones to clothing. However, there has been almost no research on the effects of these particles on animals, plants and entire ecosystems.

Self-healing concrete: This is a new concrete product infused with specialised bacteria is about to be commercialised. If use of this product becomes widespread, it could spell the end for the often unique biodiversity that currently manages to thrive in cracked concrete all around cities.

Self-healing concrete: This is a new concrete product infused with specialised bacteria is about to be commercialised. If use of this product becomes widespread, it could spell the end for the often unique biodiversity that currently manages to thrive in cracked concrete all around cities.

Energy efficient homes: Many countries are implementing large-scale retrofitting of buildings to make them more energy efficient. However, this effectively seals the building off from the outside, resulting in loss of breeding sites for wildlife such as bats and nesting birds.

Drones: The recent popularity of using drones (unmanned aerial vehicles) in cities is likely to result in issues for wildlife, such as nesting birds, which are particularly sensitive to stress and repeated aerial disturbance.

Click here for the paper:

Stanley MC, Beggs JR, Bassett IE, Burns BR, Dirks KN, Jones DJ, Linklater WL, Macinnis-Ng C, Simcock R, Souter-Brown G, Trowsdale SA, Gaston KJ. (2015). Emerging threats in urban ecosystems: a horizon scanning exercise. Frontiers in Ecology & Environment, 2015 13(10): 553–560, doi:10.1890/150229

Ecology Ngātahi members Jacqueline Beggs and Cate Macinnis-Ng were part of the Horizon-scanning exercise and are co-authors on the paper.

Dr Margaret Stanley is a Senior Lecturer in Ecology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland and is the programme director of the Masters in Biosecurity and Conservation. Her interests in terrestrial community ecology are diverse, but can be grouped into three main research strands: urban ecology; invasion ecology; and plant-animal interactions.

Dr Margaret Stanley is a Senior Lecturer in Ecology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland and is the programme director of the Masters in Biosecurity and Conservation. Her interests in terrestrial community ecology are diverse, but can be grouped into three main research strands: urban ecology; invasion ecology; and plant-animal interactions.

Speaker: Nicola MacDonald, Ngati Rehua, Ngati Wai

Speaker: Nicola MacDonald, Ngati Rehua, Ngati Wai Speaker: Dr Anna Santure, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland

Speaker: Dr Anna Santure, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland Speaker: John Innes, Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research

Speaker: John Innes, Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research

Dr Margaret Stanley

Dr Margaret Stanley

House sparrow (Image source: Fir0002/Flagstaffotos)

House sparrow (Image source: Fir0002/Flagstaffotos) Silvereye (Image source: Fir0002/Flagstaffotos)

Silvereye (Image source: Fir0002/Flagstaffotos)

Digital replacement of nature: There is a risk that nature in cities could be replaced with digital equivalents of nature, such as images and sound recordings. This gives people some of the benefits of nature, but without the maintenance and messy side of nature, however it could lead to city dwellers undervaluing nature in their immediate environment.

Digital replacement of nature: There is a risk that nature in cities could be replaced with digital equivalents of nature, such as images and sound recordings. This gives people some of the benefits of nature, but without the maintenance and messy side of nature, however it could lead to city dwellers undervaluing nature in their immediate environment. Spread of disease by urban cats: Globally, there are now more than 600 million pet cats, and the increase in pet cat ownership is resulting in the disease toxoplasma spilling over into wildlife populations, in urban areas as well as to species in more remote locations, such as the endangered Hector’s dolphin.

Spread of disease by urban cats: Globally, there are now more than 600 million pet cats, and the increase in pet cat ownership is resulting in the disease toxoplasma spilling over into wildlife populations, in urban areas as well as to species in more remote locations, such as the endangered Hector’s dolphin. Switch to LED lights: Cities across the globe are switching their lighting technology to LED lights. However, the whiter spectrum of LED lights overlaps with the visual systems of wildlife and can disrupt their physiology and behaviour.

Switch to LED lights: Cities across the globe are switching their lighting technology to LED lights. However, the whiter spectrum of LED lights overlaps with the visual systems of wildlife and can disrupt their physiology and behaviour. Self-healing concrete: This is a new concrete product infused with specialised bacteria is about to be commercialised. If use of this product becomes widespread, it could spell the end for the often unique biodiversity that currently manages to thrive in cracked concrete all around cities.

Self-healing concrete: This is a new concrete product infused with specialised bacteria is about to be commercialised. If use of this product becomes widespread, it could spell the end for the often unique biodiversity that currently manages to thrive in cracked concrete all around cities.